Genetic test to predict IBD severity in children

Thought LeadersDr. Christine OlbjørnSenior consultant,Akershus University Hospital

Thought LeadersDr. Christine OlbjørnSenior consultant,Akershus University HospitalAn interview with Dr. Christine Olbjørn, conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt, MA (Cantab)

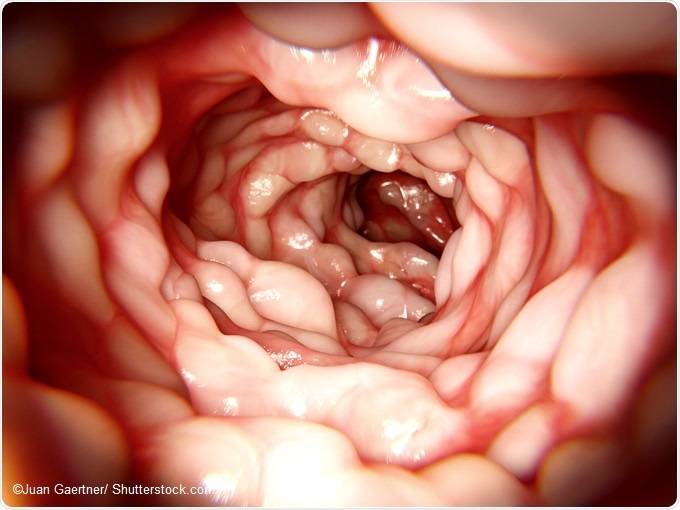

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract with abdominal pain and diarrhea being the most common symptoms. It can be challenging to diagnose as gastrointestinal complaints mimicking IBD are common.

Non-inflammatory disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome can have similar symptoms, and the threshold to perform invasive procedures like colonoscopy and upper endoscopy in general anesthesia is high in children.

IBD is often aggressive in children, and may have dramatic consequences as it can severely affect their physical, social and psychological development.

Early treatment is important to reduce the negative impact of the inflammation. IBD can, however, be difficult to diagnose. The disease course varies between patients.

Markers to identify children with IBD at high risk of a complicated disease course are needed in order to give appropriate treatment.

Therefore Norwegian scientists recent breakthrough, profiling the bacterial composition of the large bowel, the faecal microbiota, with a new test to diagnose and categorise inflammatory bowel disease, is good news for all children suffering from gastrointestinal complaints.

Why is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) often more aggressive in children than in adults and why is it difficult to predict the disease course?

Pediatric IBD typically manifests in the prepubertal age- around 12-13 years of age. This is a sensitive age as the children are supposed to have their growth spurt and go into puberty. IBD can interfere with this development.

The consequences can be detrimental, with lack of growth, weight loss and pubertal delay, as well as psychological consequences and absence from school and activities.

IBD in children is characterized by an extensive disease. IBD comprises two subgroups, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Crohn’s disease can affect all parts of the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the anus while ulcerative colitis affects the large bowel and rectum.

We have previously shown that approximately half of our patients with Crohn’s disease needed aggressive treatment within 6 months after diagnosis with biologic therapy such as infliximab in order to gain remission. This expensive and highly potent therapy is not necessary for all patients, as some can be managed with exclusive enteral nutrition and other, less expensive medications with fewer side effects.

There are several prognostic markers that are indicative of a serious disease course; such as young age (under 40 years- so all pediatric patients fall into this category), extensive disease distribution (also typical in pediatric patients), developing stenosis in the bowel, having fistulas as well as having deep ulcerations in the bowel wall. These prognostic markers are not very specific, and the individual disease course is highly variable.

In pediatric IBD patients, time is of the essence; we want to induce remission and healing of the bowel as quickly as possible in order to prevent restricted growth, delayed puberty and complications. Prognostic markers to select children and adolescents who need early aggressive treatment are needed.

Can you please outline the new genetic test for predicting IBD severity in children?

The GA-map™ Dysbiosis Test (Genetic Analysis, Oslo, Norway) uses advanced DNA profiling of feces to identify bacteria in the large bowel. In total 54 bacterial probes, based on the 16S rRNA sequence (the bacteria’s genetic profile) measure relative abundance of bacteria according to the strength of fluorescent signals detection.

More than 300 predetermined bacterial species are covered by this technology. The results are presented as relative abundances of bacteria measured as “fluorescence signal strength”.

In addition, the company has developed an Index for adult patients called Dysbiosis Index (DI is based on a comparison of analyzed data for a given patient and data from a normal adult population).

The more different the microbiota of the patient is from the normal population, the higher is the value of DI.

How does the test characterize intestinal microbiota?

For each of the analyzed samples from children with IBD, the fluorescence signal strength (FSS) from each of the 54 probes was recorded. Further, we selected 6 probes where the FSS were significantly lower in IBD patients compared to non-IBD patients.

IBD patients were given 1 point if their values were lower than for healthy children for the selected probes. The points were summarized, resulting in an Index ranging from 0 to 6 where 6 indicated that all the probes were significantly different from the values measured in healthy children.

Finally, we fitted a statistical model to estimate the odds for having IBD for those with high scores of the Index.

What did your recent study involve and what were the main findings?

The GA-map™ Dysbiosis Test has previously not been tested in children younger than 18 years of age. In order to have a reference population, we collected fecal samples from healthy children between 2 and 18 years of age.

We had fecal samples from 235 children and adolescents (80 children with Crohn’s disease, 27 with ulcerative colitis, three with unclassified IBD, 50 with gastrointestinal symptoms but no IBD diagnosis, and 75 healthy children).

These samples were analyzed using the GA-map™ Dysbiosis Test,2 and the microbiota profiles were then compared between the 110 children with newly diagnosed IBD, the 50 patients with symptoms but no IBD diagnosis, and healthy children.

We found clear distinctions between the profiles of IBD patients, non- IBD symptomatic patients and the healthy comparison group.1

The fluorescence signal strength, which indicates the abundance of different bacterial species, was significantly reduced in the children with IBD, and to a lesser degree also in those with symptoms but no IBD, compared to the healthy children.

The children with the most disturbed microbiota profiles (dysbiosis) had the most extensive IBD and were more likely to need biological therapy (TNF blockers) in the future. Patients with extensive IBD and the ones who developed complications (strictures/ fistulas) had significantly less of certain bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and more Clostridia species and Proteobacteria at diagnosis than patients with limited disease.

Children who were subsequently treated with aggressive therapy (TNF blockers such as infliximab/adalimumab) had a significantly lower abundance of the bacteria Firmicutes, Tenericutes and Bacteroidetes as well as lower abundance of Actinobacteria before treatment than those who were managed with conventional medications.

Were you surprised by the results of the study at all?

I was not surprised that the IBD patients had an altered microbiota compared to the healthy children, as this was to be expected. What did surprise me, was that the children with abdominal symptoms, but no IBD, had a microbiota profile that differed from the healthy children. It was less disturbed, i.e. less dysbiotic than the microbiota of IBD patients, but it was far from normal.

This tells me that there are many unanswered questions regarding irritable bowel syndrome and IBD. It is important that we listen to our patients, believe them when they complain of symptoms, even when we do not find inflammation or can verify a certain diagnosis.

By profiling the microbiota, we have found a correlate for their symptoms, we can show them that their microbiota is altered compared to healthy children. In the future, hopefully we can use gut microbiota profiling to target therapies for these children, with an alteration of diet, medication or with the use of pro- and prebiotics.

Moreover, we found it intriguing that there was such a clear association between a severe dysbiotic microbiota composition in newly diagnosed pediatric IBD and the need for aggressive treatment with biologic therapy. This was more than I had hoped for, and indicates that baseline microbiota profiles can be used as a prognostic tool.

Was any particular microbiota linked to Crohn’s versus ulcerative colitis?

Crohn’s disease patients had overall lower fluorescence signal strength compared to ulcerative colitis patients, but there was no single bacteria species that stood out.

What further research is needed to understand the pathogenesis of IBD in children?

I believe that the results of this study add further support to the view that gut microbial dysbiosis play a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD in children. However, we do not know what comes first; the dysbiosis or the IBD.

It is like we have discovered a new organ within the body; the gut microbiota. This organ is new to us and we need more research and a deeper understanding of how the gut microbiota impacts health and disease. The pathogenesis of IBD is complex and still not fully understood.

What impact do you think the genetic test will have?

The study indicates that this type of profiling could be clinically useful in pediatric practice and long-term patient care.

Our findings suggest that fecal microbiota profiles may be of value in differentiating IBD from irritable bowel syndrome and to identify which children are likely to develop a more severe form of IBD and which, therefore, need more intensive monitoring and possibly earlier, more aggressive treatment.

What do you think the future holds for children with IBD?

IBD is a chronic disease which might have a significant impact on patient’s health and quality of life. As we know that the microbiota plays a crucial role in the disease development I think we will learn how to utilize the gut microbiota not only in the diagnosis and follow-up of our patients but also as a treatment strategy. In the future, I believe that IBD treatment will be personalized and individualized.

Where can readers find more information?

At the web site of Genetic Analysis, there is more information of the GA-map™ Dysbiosis Test:

About Dr. Christine Olbjørn

Dr Olbjørn is an experienced pediatrician, and has worked as a senior consultant at Akershus University Hospital outside of Oslo for several years, being in charge of the pediatric gastroenterology department.

Dr Olbjørn is an experienced pediatrician, and has worked as a senior consultant at Akershus University Hospital outside of Oslo for several years, being in charge of the pediatric gastroenterology department.Her main interest is IBD and endoscopy, following patients from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up, including transition of care from adolescence to adulthood.

Currently Dr. Olbjørn is teaching medical students at the Medical School of Oslo University whilst working on her PhD thesis on paediatric IBD.

Her work elaborates on prognosis in IBD, how to stratify patients by clinical, serological and microbial markers in order to improve individualised care and outcomes.

References

- Olbjørn C, Småstuen MC, Thiis-Evensen E et al. Faecal microbiota profiles at diagnosis in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Prediction of disease severity and subsequent need of biologic therapy. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Prague, Czech Republic, 13 May 2017.

- Casén C, Vebø HC, Sekelja M et al. Deviations in human gut microbiota: a novel diagnostic test for determining dysbiosis in patients with IBS or IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42(1):71-83.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario