Differentiating sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome using biomarkers

insights from industryDr. Richard BrandonChief Scientific OfficerImmunexpress

insights from industryDr. Richard BrandonChief Scientific OfficerImmunexpressAn interview with Dr. Richard Brandon, Chief Scientific Officer, Immunexpress, conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt, MA (Cantab)

What is systemic inflammation and how many different underlying causes are there?

Firstly, it is necessary to make a distinction between systemic inflammation and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS).

SIRS consists of changes in clinical signs including an abnormal body temperature, increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate, an abnormal white cell count (either decreased or elevated), or an increase in band neutrophils.

Whereas systemic inflammation can be defined as an alteration or perturbation in the immune system, that could be detected by measuring something in the blood.

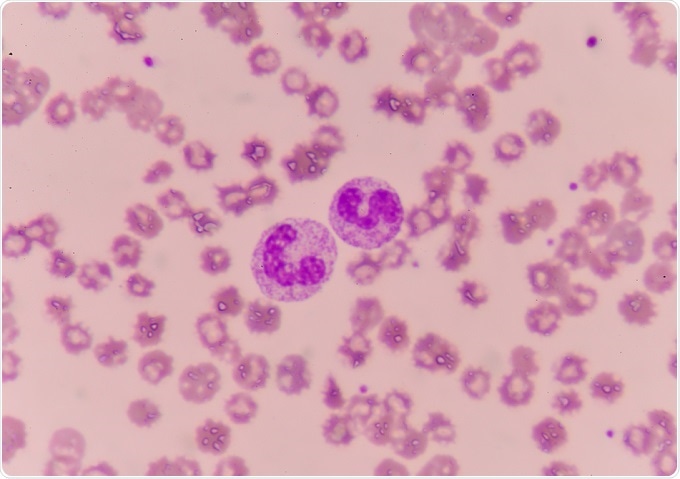

Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.comSystemic inflammation and SIRS can both be caused by lots of different things, but at the highest level you would categorize the causes into either infectious or non-infectious.

Infectious causes include bacteria, fungi, viruses, or parasites. Non-infectious causes include burns, trauma, surgery, ischemia-reperfusion, stress, sarcoidosis, asthma, etc.

The difference between infectious and non-infectious can sometimes be a bit of a blurred line. This is because the body has a microbiome, and when you get damaged tissue, there's often a certain bacterial or infectious element to it as well.

What impact do sepsis and SIRS have on the population?

Sepsis is the most expensive condition in U.S. hospitals costing our healthcare system over $15 billion per year. Sepsis is also the biggest killer of children under 5 worldwide.

The prevalence of SIRS in hospitals is also very high - about 30% of people in hospital have an episode of SIRS during their stay. Clinicians then have to determine whether these patients have an infection or not.

Sepsis, in the United States, has an eight times higher mortality than any other condition. It is the number one killer of people in intensive care. Sepsis needs more attention, and people need to become more aware of it. There is a need for better diagnostics, better and more directed care, and better antibiotic use.

Why do you think sepsis is not more well-known?

The clinical definition of sepsis has changed over the years. A lack of a clear definition of what sepsis is, and a lack of gold standard diagnostic for sepsis are possible factors contributing to its low-profile status. Other terms used for sepsis include blood poisoning, toxic shock syndrome, endotoxemia, or blood stream infection.

Because sepsis often affects the elderly, usually when they have some other condition, it is perhaps talked about less. The tragedy of the lack of awareness of sepsis is in children. That’s where people need to be made more aware of it in particular.

The fact that sepsis isn't well-known emphasises that it needs more promotion as a potential killer.

Credit: toeytoey/Shutterstock.com

Credit: toeytoey/Shutterstock.comWhy can it be difficult to establish the underlying cause of systemic inflammation?

The main reason that infectious and non-infectious causes are difficult to distinguish is because patients present with the same clinical signs. Clinicians therefore can't tell the difference between an infectious and a non-infectious case. An infectious cause of systemic inflammation, like sepsis, is a medical emergency which has to be treated as soon as possible.

Another reason is that current diagnostic tests aren't particularly good. For instance, for sepsis there is no gold standard diagnostic.

Blood culture is used to diagnose sepsis which involves taking blood from a patient and then trying to grow a microorganism. However, blood culture is a gold standard diagnostic for bacteremia, rather than for sepsis. Blood culture has high false positive and false negative rates. Up to 90% of all blood cultures taken from patients suspected of having an infection are negative. Also, in many instances when a blood culture is positive it is due to contamination rather than because of the patient actually having an infection.

What challenges does this pose for diagnosis and treatment?

The fact that there is no diagnostic gold standard for sepsis makes it very difficult to diagnose, and the treatments for an infectious condition versus a non-infectious condition are quite different.

Because these patients present with similar sorts of clinical signs, many patients in hospital are on antibiotics, and a large proportion of those are on antibiotics needlessly. But it also could mean that certain patients are misdiagnosed. Either they're diagnosed with having a non-infectious condition, when they actually have an infectious condition, or vice versa. This leads to patients getting the wrong treatment or not getting treatment at the right time.

Sepsis is a medical emergency, and the sooner it is treated, the lower the mortality. For septic shock for instance, every hour a patient is not being treated leads to an increase in mortality.

How does the required response to sepsis differ from systemic inflammatory response syndrome?

The response to sepsis and non-infectious SIRS are different.

Sepsis has to be treated as soon as possible. It involves the immediate use of empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics and fluid support while waiting for the results of blood culture and antibiotic sensitivity. Other treatments for septic shock include the use of vasopressors and organ support. In some instances, which is still controversial, some patients get steroids.

Patients with non-infectious Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome shouldn't be on antibiotics. They could be given anti-inflammatory medications and other support. They may also need to undergo some other diagnostic procedure to determine what is the cause of non-infectious SIRS.

Can you please outline the recent investigation of a four-biomarker blood signature to discriminate viral and non-viral causes of systemic inflammation?

There are a number of published articles in the literature that describe biomarker signatures that can distinguish between bacterial and viral infection, but they either consist of a large number of biomarkers, or do not take into consideration that patients could have a non-infectious condition. In our most recent paper, we discovered a four-gene biomarker signature in blood that is very specific to viral infection in a heterogenous population of patients that could have other infections or non-infectious Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome.

We thought specificity was important because patients that are suspected of infection usually present with clinical signs of SIRS. We also thought it was also important that the signature consisted of a limited number of biomarkers.

A signature consisting of a limited number of biomarkers means that it lends itself more to translation onto a point-of-care machine. Testing on a point-of-care machine means that it can be done quickly and closer to the patient, which is an important part of managing a patient with suspected sepsis.

It was a large study where we used over 3000 subjects to discover the signature, and then we validated the signature on another 600 subjects, including patients enrolled in two clinical trials in adults and children.

Did the signature demonstrate a meaningful distinction?

One of the key attributes of this viral signature is that we've demonstrated that it has diagnostic power across all seven Baltimore virus classification groups.

In the Baltimore classification of viruses, there are seven groups. Classification is based on whether a virus is DNA or RNA, double-stranded or single-stranded, or whether it is a negative or positive-sense.

This particular signature works across all of those different types of viruses. A patient could be infected with any type of virus and our signature could still detect that that person had systemic inflammation caused by a virus.

The study also demonstrated that the signature is able to detect a viral infection very early in the course of infection, before viremia and before clinical signs develop.

Another key finding was that the signature worked in a number of different tissues, including blood, liver, and in vitro culture. It also worked in different mammals, including macaques, monkeys, pigs, rats, and mice.

We're calling it a pan-viral signature; it is very specific, and it can be used very broadly.

What impact will this analysis have?

We didn't intend that the viral signature was to be used alone. We always intended that it'd be used in combination with our SeptiCyte™ LAB signature.

SeptiCyte™ LAB is an FDA-cleared assay that provides a probability of a patient having sepsis or non-infectious SIRS. It is also a four-biomarker signature. In the last part of our paper, we analysed a public dataset using the combination of our viral signature and SeptiCyte™ LAB. In this dataset patients had acute respiratory illness due to either bacterial, viral or non-infectious causes. Using the two signatures in combination separated out these patients very well based on etiology.

Using these two assays in combination, clinicians can be provided with a probability of whether a patient has either sepsis or SIRS, and whether the sepsis was caused by a virus or not. In combination, these signatures may lead to better management of patients that are suspected of having an infection.

What do you think the future holds for patients suspected of sepsis?

I think that the future for patients suspected of having sepsis it is very positive.

Whilst I don't think the prevalence of sepsis is going to necessarily decrease in adults or the elderly, the largest impact I hope to see as a result of better awareness, diagnostics, prognosis, monitoring and treatment will be in children less than five years of age.

Using our viral signature in combination with our SeptiCyte lab signature, especially on a point-of-care platform, will lead to faster and more accurate diagnosis of sepsis, which will ultimately lead to faster and more directed treatment.

When the test costs come down, patients can ultimately be monitored.

For instance, patients on chemotherapy are particularly prone to getting infectious conditions. If they could monitor themselves on a regular basis to see whether they were getting an infection, then they could be treated much earlier, and there would be less side effects of chemotherapy.

The use of biomarkers can provide a prognosis for sepsis, but patients can also be stratified. Patients in intensive care and wards can be categorized or stratified into different levels of treatment or management requirements.

The future for patients with suspected sepsis is very positive, especially with the use of host response signatures in combination with point-of-care machines for better and earlier diagnosis.

What is Immunexpress’ vision?

The original company vision was to be able to aid clinicians in making better diagnoses, especially for patients suspected of infection, which would then lead to better patient outcomes.

The company's vision is for our tests to be a clinician's first choice of diagnostic procedure when they suspect that a patient has infection. This would then guide a clinician on how to manage a patient and what other diagnostic tests might be of use.

In addition, I mentioned earlier that sepsis doesn't have a diagnostic gold standard, I would like to see the Immunexpress tests being a new gold standard for diagnosing sepsis based on host response.

Where can readers find more information?

- www.sepsis.org

- Our website - http://www.immunexpress.com/

- The Centers for Disease Control - https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/index.html

- The World Health Organization - http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/11/10-077073/en/

- Journal of the American Medical Association - Blood Culture Collection for Suspected Bacteremia - http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/1558267

About Dr. Richard Brandon

Richard is currently co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer for Immunexpress, a Seattle-based company commercializing host response assays for sepsis diagnosis. He is a qualified veterinarian and gained his PhD in Biochemistry from the University of Queensland, and his MBA from the Queensland University of Technology.

After a brief period in veterinary practice, his career has focused on molecular immunology / genetics and its application in understanding the immune response to infection.

Before co-founding Immunexpress, he has spent time as a veterinary pathologist, a post-doctoral researcher at Cornell University and The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and in an equine-DNA parentage-testing laboratory.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario